A successful partnership between a local stakeholder group and a private company in one of India’s largest cities, illustrates how it is possible for genuine corporate social responsibility to help make meaningful, rapid and lasting change. The Gurgaon Water Forum, a public engagement initiative, has carried out continuous outreach in Gurugram for many years; now it has teamed up with RSPL Limited, a mixed business group, to finance, construct and manage a rain-water harvesting, recharge and drainage system to prevent local flooding. Eventually, the project will be handed over to local government, but for now, it is an example of the results from India’s Companies Act 2013, which mandates that firms over a certain size must contribute a percentage of their post tax profits to social responsibility work that is aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In July, 2016, flash floods affected parts of Gurugram, India’s Millennium City, with such severity that the local administration had to issue prohibitory orders to control traffic jams, shut down schools, and stop incoming traffic from the national capital of Delhi. The Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) has also officially declared Gurugram in the ‘dark zone’ where groundwater has been over-exploited and borewells can no longer be operated without special permission. The situation in Gurugram is not unique and similar problems plague other Indian cities. However, Gurugram, which is also a part of the national capital region, has had legislation mandating rainwater harvesting in all commercial structures and residential colonies since the mid-2000s. The flash floods of 2016 brought back the city’s attention to the necessity of reviving local watersheds, building and maintaining rainwater harvesting (RWH) structures, and retrofitting the city to better fit its local hydrogeology.

As much of the city and its infrastructure has been built using private money, Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs) have been important stakeholders in the city’s governance to pressurise both private developers and the local government for access to services. RWAs in many areas have been instrumental in creating and maintaining RWH structures to tackle local water logging problems. However, RWAs tend to be more prevalent in high and middle-income colonies; most low-income colonies lack the requisite support or financial means to organise themselves in order to demand better amenities from the local government.

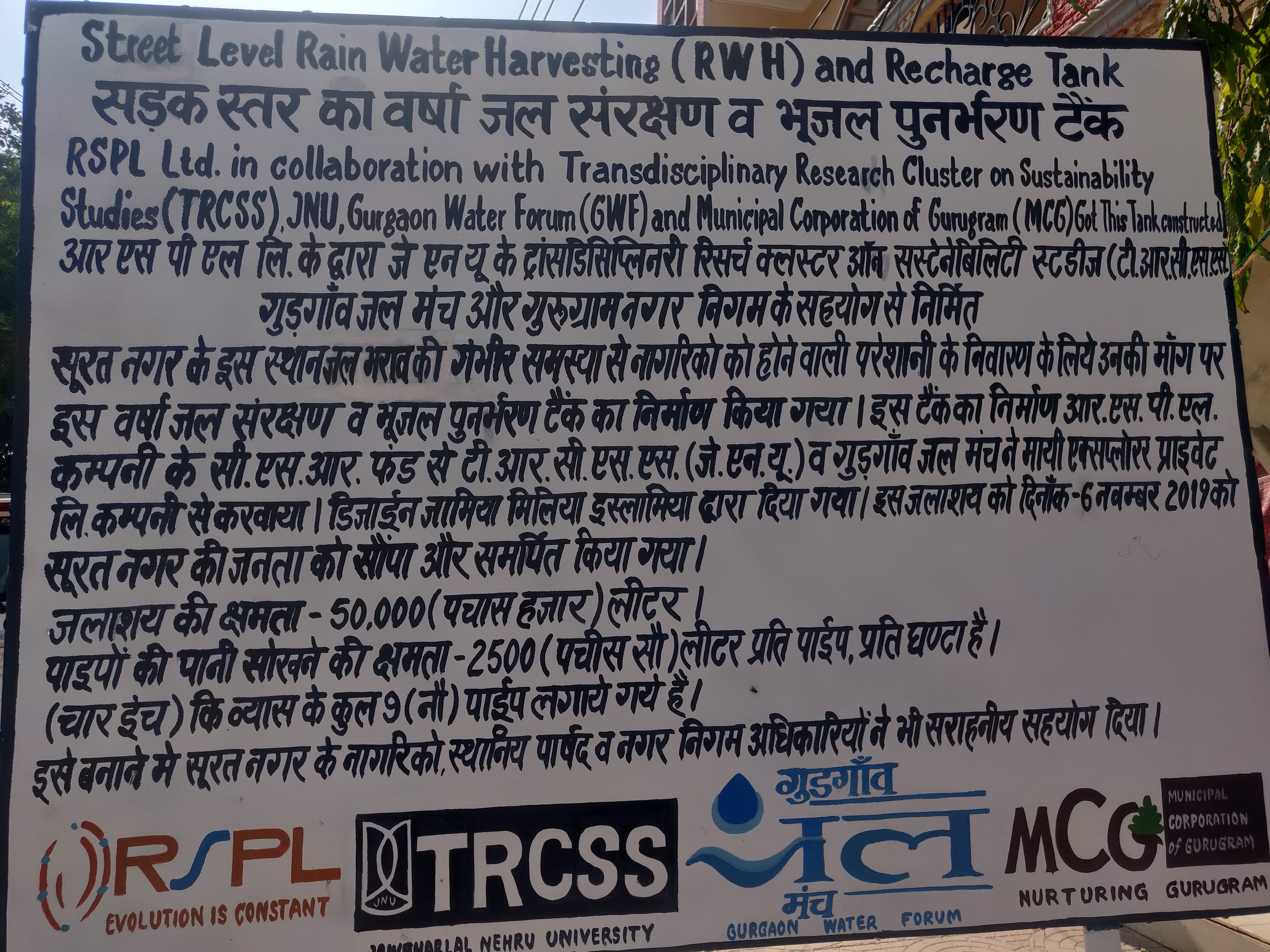

Gurgaon Water Forum’s (GWF) continuous engagement in Gurugram through T-Labs (Transformation Labs are a method of collaborative and innovative working coined in the US’s Silicon Valley) and public consultations have ensured that they target localised flooding in low-income residential areas that are often neglected by the local administration and by the media. GWF’s approach to a sustainable transition keeps water at its core, keeping people with technical expertise and experience in negotiating with the local administration on board even after the project has been completed. When GWF needed financial resources, it was able to turn to RSPL Limited, a business conglomerate, for assistance under the firm’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policy. GWF selected the site at Surat Nagar, Gurugram and a street level RWH and recharge structure was constructed to ease the problem of water-logging in the area.

GWF and RSPL Limited is currently responsible for maintenance of the structure for the first two years, after which the site will be officially handed over to Municipal Corporation of Gurugram (MCG) for annual maintenance. It is important to point out that CSR is still a fairly blunt tool and is not a guarantee for success and social justice. Many state-based, community-based and company-based factors determine the likely success of such initiatives and the often huge power disparities between the businesses and local communities mean that structures need to be in place to redress this inequality.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with their expansive range of targets, presents an implementation challenge and requires massive infrastructural investment if we are to reach the goals. Recognising that the mammoth task can only be achieved by having all stakeholders on board, SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) envisages multi-stakeholder partnerships as crucial for mobilising and sharing expertise, technologies and financial resources. With limited sources of finance from governments, especially in developing countries, it is important to mobilise the private sector to finance the huge expenditure (estimated to the tune of $5 trillion) which is required to meet the Global Goals. As some commentators note, the SDGs represent a shift in the UN’s policy and have been explicitly designed to bring the private sector in as a stakeholder in addressing these vast, cross-sectoral challenges.

While financing for the SDGs by the private sector is usually conceived only at the scale of public-private partnerships (PPP) for infrastructural development, CSR is another important interface where multi-stakeholder forums can thrive and through which local transitions can be made. Formal PPP arrangements, while recognising in theory that the engagement of civil society actors is crucial for effective governance, leave little or no room for substantial influence by civil society actors in the actual governance of any project. CSR provides an opportunity to leverage the comparative advantages of academic institutions, NGOs, other civil society actors, and communities at large at the grassroot level to map out systemic challenges and solutions from a more holistic perspective.

The success of achieving the Global Goals rests on the successful localisation of their targets and indicators. To date, the role of local and regional governments (LRGs) have been emphasised in the process of monitoring and reporting progress of the goals. The focus needs to shift to enable local governments to set the agenda and prioritise targets that reflect local contexts and local needs. For example, drinking water supply, sanitation, and transport systems have been high on the agenda of both the national and urban local governments in India and these have been prioritised in successive action plans. To draw the attention of local governments to other bottlenecks in city planning requires careful mapping of development gaps and evidence-based prioritisation of goals. Given that this can be a politically fraught exercise, a broad-based coalition of engaged citizens such as the GWF can demonstrate how important it is to tweak the goals to make them context-specific and to target cross-sectoral links to achieve the best outcomes.

The 2016 flooding of arterial roads in Gurugram drew the attention of national media and spurred action by district authorities even as water-logging continues to be a lived reality for many areas across the city. Gurugram’s ad-hoc mode of development (see link to our earlier case study) has meant little regard for the kind of systemic planning that would have included effective drainage systems. Gurugram’s drainage system involved a series of natural and artificial channels, plus small, sometimes temporary “check dams” that helped slow down and capture rainwater as it flowed down the Aravalli Range, recharging groundwater and preventing flooding in the area.

In the past four decades, the city has lost more than half of its water bodies; these have reduced in number from 519 according to records of the Survey of India (1976) to around 215 water bodies currently surviving. Many of these have been partially encroached upon by individuals and, in some cases, by the district or local administration itself. Others have been completely encroached upon by private developers. Speculative real estate development has resulted in a massive demand for land and since most of the city’s water bodies are seasonal in nature, they have been filled in and ‘developed’ into land parcels for residential or commercial use. Encroachment into watersheds has led to many water bodies drying up or becoming conducive spots for dumping waste water or garbage from surrounding residential areas or household industries.

Flooding of arterial roads and localised water-logging is also a result of inadequate planning of trunk infrastructure in the city. As the city developed in spurts – mostly in the shape of isolated private gated communities, buffered by urban villages and unauthorised colonies – trunk infrastructure is often only built as an afterthought and is not integrated with other systems. There can be a back flow of water from separate drain systems due to them being inadequately connected. This regularly causes localized waterlogging in several areas such as along Khandsa Nallah.

One of the primary factors that facilitated this complementary partnership between a multi-stakeholder forum such as GWF and a business conglomerate is the legal framework. India is one of the few countries that has legally mandated corporate social responsibility as part of the Companies Act, 2013. The Act stipulates that companies with a “net worth of rupees five hundred crore or more, or turnover of rupees one thousand crore or more or a net profit of rupees five crore or more during any financial year constitute a Corporate Social Responsibility Committee” and spend at least 2% of their average net profits from the three preceding financial years, in pursuance of its Corporate Social Responsibility Policy. While CSR has always been interpreted as a voluntary contribution to overarching goals of sustainable development, formally mandating it via this legal route has streamlined the process and has opened the door for long-term, meaningful engagements between different stakeholders instead of sporadic efforts.

While the Indian Government’s CSR policy preceded the official declaration of SDGs in 2015, the ten broad areas listed in the Act’s Schedule VII broadly align with the SDGs. For example, the CSR Policy’s sixth activity – ensuring environmental sustainability – aligns with SDG 7 (Affordable and clean energy), 11 (Sustainable cities and communities), 12 (Responsible production and consumption), 13 (Climate action), 14 (Life below water), and 15 (Life on land). Broad alignment between the SDGs and India’s CSR Policy means that it has become easier for companies to contribute to the national level targets whilst also integrating the Global Goals for effective tracking and reporting at the international level.

The Act also mandates that preference should be given to local areas and areas where any company operates in implementing the CSR policy. It is here that Gurugram’s location as home to numerous corporate offices and manufacturing units, ranging in size from Fortune 500 companies to home grown brands, provides the perfect opportunity. By tapping into resources from the private sector, partnerships can be forged that make tangible differences if nurtured with a genuine vision. Given the city’s trajectory of urbanisation, private actors have always played a crucial role in its governance – a fact that has also been acknowledged by the local government. The local government works proactively to encourage innovative and cost-effective CSR sponsored projects to address the city’s challenges, although plans for a separate secretariat for projects funded with CSR never took off.

This story of change was contributed by Bikramaditya K Choudhary, Assistant Professor, CSRD/SSS, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and Ms Uma Dey Sarkar

The Companies Act, 2013, s. 135, available at http://www.mca.gov.in/Ministry/pdf/CompaniesAct2013.pdf

Sharma, K. (2016), Public-private partnerships and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, available at https://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/public-private-partnerships-and-2030-agenda-sustainable-development

Kramer, M. R., R. Aggarwal, and A. Srinivas (2019), Business as Usual will not Save the Planet, available at https://hbr.org/2019/06/business-as-usual-will-not-save-the-planet

Global Taskforce of Local and regional Governments (2019), Local and Regional Governments Report to the 2019 HLPF, Towards the Localization of the SDGS, available at https://www.uclg.org/sites/default/files/towards_the_localization_of_the_sdgs_0.pdf

Kumar, A. (2014), Gurgaon to tap into CSR to address city’s challenges, The Hindu (Delhi), available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/gurgaon-to-tap-into-csr-to-address-citys-challenges/article6257119.ece

Gurugram Metropolitan Development Authority (2019), Report on Waterbodies of Gurugram District available at http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/ReportonWaterbodiesofGurugramDistrict.pdf

Newell, P. 2005, Citizenship, accountability and community: the limits of the CSR agenda. International Affairs, Volume 81, Issue 3, May 2005, Pages 541–557 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00468.x